When we talk about training approaches, we often focus on the big picture - periodization (or whether it’s needed). This long-term view is important, but it can lead us to overlook the structure of the training week itself. We love digging into the macrocycle, but the microcycle - the weekly setup - often gets designed once and then remains the same.

I’m guilty of this myself. But maybe it’s time to zoom in, examine why your training week looks the way it does, and consider whether it could be improved. Small tweaks could have a positive impact for you and your athletes, including bigger strength lifts, sharper technique, and looking more jacked.

Do I think this process is a magic bullet? By no means. But there are probably some ways you could use these principles to help individualize your approach to programming, ultimately building successful microcycles.

Programming 101: GAS and the Fitness-Fatigue Model

One of the first concepts we come across when learning about the science of strength training is General Adaptation Syndrome (GAS), a model developed by Hans Selye in the earlier parts of the 20th century. Even with its limitations, it can help us understand key concepts in training, recovery, and adaptation.

The GAS model shows us that after encountering a stressor (in our case, training), there’s an initial dip in performance due to fatigue, followed by a rebound as adaptation occurs. In Figure 1, you’ll see the fitness-fatigue model: the red line essentially mirrors the GAS process, while the dotted blue and solid green lines represent the fitness and fatigue after-effects, respectively. Fitness can be understood as the positive adaptations gained from training (e.g., changes in muscle size), while fatigue is viewed as the negative “tax” resulting from the same dose of work.

For further background reading on both GAS and the Fit-Fat model, check out

Cunanan et al. (2018) and Chiu & Barnes (2003).

Figure 1: The model above illustrates a single training session, but when we consider a week (or more) of training, we can imagine the cycle repeating with each following disruption.

If we stack too much training stress too close together, performance decreases as fatigue accumulates - preventing us from fully realizing fitness adaptations. If we space training sessions too far apart, we simply return to baseline - never building on the improvements. It’s a balancing act; too much stress can hinder progress, while too little fails to overload the system.

This tells us that to help an athlete adapt and perform better, we need to dose training effectively. The challenge is that the right amount for one person is likely different for another, and this depends on two main factors:

- Training history

- Individual differences

For a well-trained athlete, recovery ability is often higher. This means they can typically handle more training sessions per week and/or greater stress within each session. The opposite holds true for an untrained lifter, who usually has a lower capacity for recovery. They may need to train less frequently and/or with lower training stress per session to see adaptation.

While these are good general guidelines, some people simply handle higher volumes and intensities of training than others. Genetics may play a role, or perhaps it’s due to higher stress levels outside of training. Whatever the reason, knowing your athletes is essential for making smart, individualized decisions.

Programming 102: Exercise Selection and Frequency

With the above in mind, it’s important to remember that while overall training stress contributes to an athlete’s general fatigue, we also need to consider specificity when designing a training week. It doesn’t take a rocket scientist to know that if you train one part of the body really hard, repeating that the next day may not be ideal. Go ahead, try it and let us know what you think…

Although, sometimes this overlap is intentional; for example, athletes may attend training camps where they face a high volume of similar training stress, but these instances are usually followed by recovery periods.

Example:

Morning Session

- Block Power Snatch, 3/2 at 70-75%

- Block Power Clean, 3/2 at 70-75%

- Back Squat, 4/2 at 80-82.5%

Afternoon Session

- Hang Snatch Above Knee, Heavy Single

- Clean + Jerk, 90% Single

- Clean Pull, 100% for 3/2

In a regular training week, though, it’s wise to think about how to spread out sessions to allow the athlete to perform that movement at a high standard again - without the impact of lingering fatigue.

For example, an athlete squatting three times per week might do so on Monday, Wednesday, and Friday, with the hardest session on Monday and the easiest on Wednesday. This setup allows them to tackle their toughest session when they’re freshest and ensures they have adequate recovery throughout the week.

Example:

Monday

- Beltless Back Squat, 7/3 at 70-75%

Wednesday

- Front Squat, 5/2 at 77.5-82.5%

Friday

- Back Squat, 4/4 at 75-80%

Now, if we consider different muscle groups, such as pressing movements, squats will likely have minimal impact on these. So, sticking with the example above, pressing movements could be trained on Tuesday, Thursday, and Saturday. While some fatigue from squats may remain, it’s unlikely to significantly affect pressing performance - and vice versa.

Structuring Training Days

Within each training week, there are likely some key training sessions. These are the sessions considered priority work, probably competition exercises, and likely the highest-intensity strength-focused work.

Over the course of a week, it’s important to consider where these sessions go and where lower-priority days may be placed. For some lifters, you’ll likely only have two or three sessions total, in these cases this isn’t a major concern. However, other lifters may train five or more times per week - this is where it becomes of utmost importance to get this right.

Similar rules apply to what we discussed with exercise selection and frequency above - the more space you can have between key sessions, the better. However, it is often feasible for a powerlifter, for example, to have a heavy squat day followed by a heavy bench day. But if sessions are full-body in nature, a harder session should naturally be followed by a session with a lower training load.

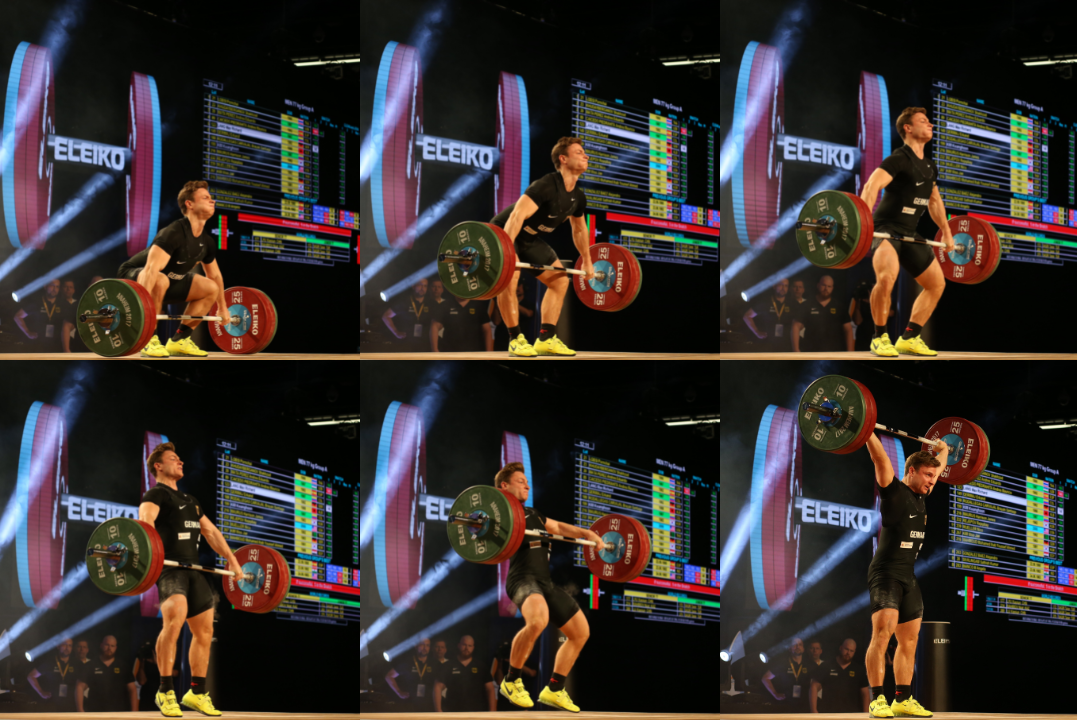

Weightlifting Example:

Monday

- Snatch Complex, working up to 88-92%

- Block Power Clean, 3/3 at 70-75%

- Back Squat, top triple with the first rep paused (RPE 8)

- Pressing Accessories

Tuesday

- Tempo Power Snatch, 4/2 at 70-75%

- Jerk from Blocks, 5/3 at 75-80% (building after the first 3)

- Clean Pull, 4/2 at 100-110%

- Rowing Accessories

Powerlifting Example:

Thursday

- Safety Bar Squat, 3/5 building to a top set

- Tempo Safety Bar Squat, 3/5 at RPE 6-7

- Romanian Deadlift, 4/4 at RPE 6-7

- Machine Leg Curl, 3/10 at RPE 7-8

- Hip Extension, 3/12

Friday

- Medium Grip Bench Press, 3/5 building to a top set at RPE 7-8, 2 down sets at 85-90%

- Incline Bench Press, 3/8 at RPE 7-8

- Barbell Row, 3/8 at RPE 7-8

- Machine Row (lat-focus), 3/10

It’s a balancing act, and there’s no golden rule here, but the idea of sufficient recovery between primary (or high-stress) sessions is the guiding principle. It’s also worth noting that sufficient recovery doesn’t mean full recovery; athletes are likely to carry some residual fatigue during a training week.

Programming 201: Building a Microcycle

With the main considerations of the design out of the way, let’s work through some examples. Remember that none of the examples are ‘perfect’, but intended to show how things could be done.

Let’s start with a conceptual three day week with 100 ‘training units’. With a three day week, it is much easier to balance training and recovery – perhaps a full-body training approach can be taken.

Putting it together, we could have two more challenging days and one easier day, something like:

Alternatively, given we can have a couple of days between sessions, we might opt for something like this to spread the training load across the week:

Now, let’s say we want to add more total training load and move to four days, increasing our total ‘training units’ to 130.

With four days, we can no longer have a full day off between sessions, so we need to better manage the overall training load per day. Here’s one example:

In this scenario, Saturday is the toughest day (assuming the athlete has more time on Saturdays). Monday and Thursday are medium days, with Tuesday being the easiest of the four.

Examples training weeks could be:

Weightlifter

- Monday: Snatch variations, Squats

- Tuesday: Jerk variations, Presses

- Thursday: Clean variations, Squats

- Saturday: Snatch, Clean and Jerk, Squats

Powerlifter

- Monday: Secondary Squat

- Tuesday: Secondary Bench

- Thursday: Secondary Deadlift

- Saturday: Squat, Bench, Deadlift

This setup reasonably distributes the training load across the week while also managing the exercises and muscles being trained, ensuring the athlete can give a solid effort each session.

An alternative approach for an athlete who cannot train on weekends might look like this:

In this case, we have two harder days each followed by easier days.

Examples training weeks could be:

Weightlifter

- Monday: Snatch Variation, Clean, Squat

- Tuesday: Jerk, Pressing

- Thursday: Snatch, Clean variation, Squat

- Friday: Power Snatch and/or Power Clean and Jerk

Powerlifter

- Monday: Squat, Secondary Deadlift

- Tuesday: Bench Press

- Thursday: Secondary Squat, Deadlift

- Friday: Secondary Bench Press

These examples are intentionally abstract and high-level. The key is to reflect on why you arrange your training week the way you do - and to consider if there are ways you could improve it.

Final Thoughts

Designing a training week is a balancing act; it’s about more than just following a set of principles. It’s about adapting to the needs of your athletes. Look for areas where fatigue might be limiting performance, and see if adjusting session timing or load distribution can help.

Remember, there’s no one-size-fits-all weekly structure. Pay attention to athlete feedback, monitor progress, and be open to making changes to your usual setup. Otherwise, you could be setting yourself up for failure.

.jpg)

.png)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.png)